By: Tao Steven Zheng (郑涛)

Chinese Numerals and the Decimal System

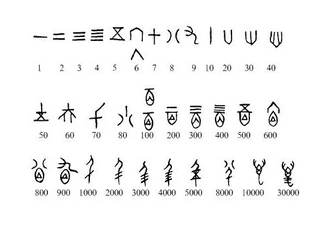

The Chinese adopted a decimal (base-ten) numeral system as early as the fourteenth century BC, during the Shang dynasty (c.1600 – 1046 BC). This is evidenced by the earliest literary inscriptions, called jiaguwen (甲骨文, “oracle bone script”), which were etched on durable media such as tortoise plastrons and the shoulder bones of cattle. Many of the jiaguwen archival documents recorded special events, oracle queries, as well as astronomical observations. Fortunately, the Shang scribes left behind records that include numerals (Figure 1).

There were originally thirteen distinct symbols for the numbers one to nine, ten, hundred, thousand, and myriad (ten thousand). For example, the number 51238 would be literally expressed as five-myriad one-thousand two-hundred three-ten eight 五万一千二百三十八 (wu wan yi qian er bai san shi ba). Symbols for larger powers of ten and zero would appear in later dynasties. Table 1 shows the original Chinese numerals and their equivalent Hindu-Arabic numeral.

Table 1. Chinese numerals

| Number | Hindu-Arabic Numerals |

| 一 yi | 1 |

| 二 er | 2 |

| 三 san | 3 |

| 四 si | 4 |

| 五 wu | 5 |

| 六 liu | 6 |

| 七 qi | 7 |

| 八 ba | 8 |

| 九 jiu | 9 |

| 十 shi | 10 |

| 百 bai | 100 |

| 千 qian | 1000 |

| 万 wan | 10000 |

Counting Rods

Figure 2. Ivory counting rods

By the Spring-Autumn (771 – 476 BC) and Warring States period (476 – 221 BC), Chinese arithmeticians have transitioned to the use of counting rods for representing numbers and performing calculations. There were many names for counting rods: chou-suan (筹算), chou-ce (筹策), suan-ce (算策), and suan-zi (算子). Each name suggests that they were used for calculation and planning. The counting rods were made of a variety of materials, from wood and bamboo to more expensive materials such as bone, bronze, and ivory (Figure 2).

Figure 3. Counting board with counting rods

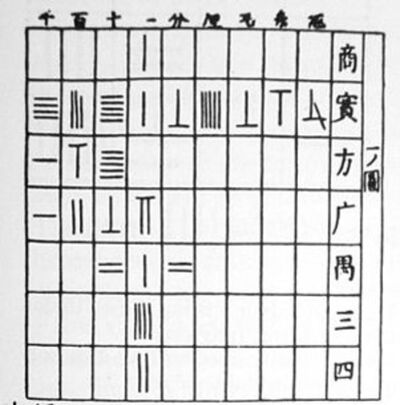

The counting rods were arranged on a flat surface such as a table or the ground; more elaborate surfaces included counting boards that included marked square cells to demarcate rows and columns (Figure 3). According to the Sunzi Suanjing (孙子算经, Sunzi’s Mathematical Manual), rods representing the digits of even powers of ten are placed vertically, while rods representing digits of odd powers of ten are placed horizontally.

| 凡算之法,先识其位,一从十横,百立千僵,千十相望,万百相当。 | For the method of computation, one must first know the positions [of the rod numerals]. The units are vertical and the tens horizontal, the hundreds stand and the thousands prostrate; thousands and tens look alike, and so do ten thousands and hundreds. |

This rule was adopted to avoid confusion when performing arithmetic calculations. Any place value where zero would appear were simply left blank; this was called kong (空, literally “empty” or “void”). The concept and application of negative numbers first arose in ancient China. As early the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), coloured rods were used to differentiate positive numbers from negative numbers (Figure 4). Alternatively, a single rod set diagonally across the rods representing a given number could also signify a negative number. According to Liu Hui’s commentary of the Jiuzhang Suanshu (九章算术, Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art):

| 今两筭(算)得失相反,要令正负以名之。正算赤,负算黑。否则以邪(斜)正为异。 | Two kinds of counting rods represent the mutual opposites of gains and losses. Let them be named positive and negative. The positive rods are red, and the negative rods are black. Otherwise, they can be differentiated by being placed slanted or upright. |

Chinese counting rods were not only used for performing arithmetic. By the Han dynasty, counting rods were used to represent the coefficients of simultaneous linear equations, much like how matrices are used in modern mathematics. During the Song dynasty, Chinese mathematicians went as far as developing a notation for representing polynomial equations.

Arithmetic with Counting Rods

Counting rods served as a tool for carrying out the steps of computation, which enabled the arithmeticians to perform calculations of arbitrary complexity with relative ease. Systematic and efficient algorithms for addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division were developed to perform such tasks. More remarkably, algorithms for calculating square roots and cube roots were developed by the Han dynasty.

Problem Study 1: Multiplication with Counting Rods

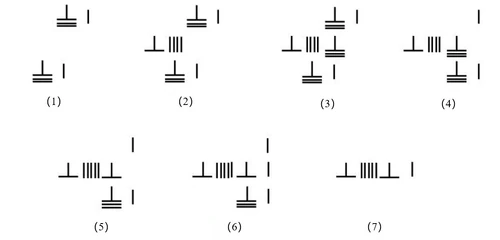

The following problem from the Sunzi Suanjing (Chapter 1, Problem 16) demonstrates how ancient Chinese arithmeticians performed multiplication and addition. When performing multiplication, the two multiplicands are set in the upper position (上位 shang wei) and lower position (下位 xia wei); the product rests in the middle position (中位 zhong wei).

There are three positions when implementing rod numerals to perform multiplication and division: upper position (上位 shang wei), middle position (中位 zhong wei), and lower position (下位 xia wei). When multiplying two numbers, rods set in the upper position represent the multiplier; rods placed in the lower position represent the multiplicand; lastly, rods placed in the middle position represent the product. Figure 5 illustrates the multiplication algorithm using counting rods.

| 九九八十一,自相乘,得几何?

|

Nine times nine makes 81. What is the amount when this is multiplied by itself?

|

(1) Set up the two positions [upper position and lower position].

| 千 | 百 | 十 | 一 | |

| 上位 | 8 | 1 | ||

| 中位 | ||||

| 下位 | 8 | 1 |

(2) The 8 in the upper position calls the 8 in the lower position, eight times eight makes 64, so put down 6400 in the middle position.

| 千 | 百 | 十 | 一 | |

| 上位 | 8 | 1 | ||

| 中位 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 下位 | 8 | 1 |

(3) The upper 8 calls the lower 1: one times eight is 8, so put down 80 in the middle position.

| 千 | 百 | 十 | 一 | |

| 上位 | 8 | 1 | ||

| 中位 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 0 |

| 下位 | 8 | 1 |

(4) Shift the lower numeral one place [to the right] and put away the 80 in the upper position.

| 千 | 百 | 十 | 一 | |

| 上位 | 1 | |||

| 中位 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 0 |

| 下位 | 8 | 1 |

(5) The upper 1 calls the lower 8: one times eight is 8, so put down 80 in the middle position.

| 千 | 百 | 十 | 一 | |

| 上位 | 1 | |||

| 中位 | 6 | 4 | 8 + 8 | 0 |

| 下位 | 8 | 1 |

| 千 | 百 | 十 | 一 | |

| 上位 | 1 | |||

| 中位 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 0 |

| 下位 | 8 | 1 |

(6) The upper 1 calls the lower 1: one times one is 1, so put down 1 in the middle position.

| 千 | 百 | 十 | 一 | |

| 上位 | 1 | |||

| 中位 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 1 |

| 下位 | 8 | 1 |

(7) Remove the numerals in the upper and lower positions leaving 6561 in the middle position.

| 千 | 百 | 十 | 一 | |

| 上位 | ||||

| 中位 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 1 |

| 下位 |

Problem Study 2: Division with Counting Rods

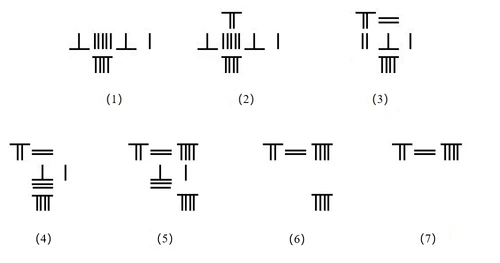

The following problem is from Sunzi Suanjing (Chapter 1, Problem 17). Similar to multiplication, three positions are used; however, this time the middle position represents the dividend (实 shi), the lower position represents the divisor (法 fa), and the upper position represents the quotient (商 shang). Figure 6 illustrates the division algorithm using counting rods.

| 六千五百六十一,九人分之,问:人得几何?

|

Divide 6561 evenly among 9 people. Question: How much does each person receive?

|

(1) First set 6561 in the middle position to be the dividend (实 shi). Below it, set 9 persons to be the divisor (法 fa).

| 千 | 百 | 十 | 一 | |

| 上位(商) | ||||

| 中位(实) | 6 | 5 | 8 | 1 |

| 下位(法) | 9 |

(2) Put down 700 in the upper position. The upper 7 calls the lower 9: seven nines are 63, so remove 6,300 from the numeral in the middle position.

| 千 | 百 | 十 | 一 | |

| 上位(商) | 7 | |||

| 中位(实) | 6 | 5 | 8 | 1 |

| 下位(法) | 9 |

(3) Shift the numeral in the lower position one place [to the right] and put down 20 in the upper position.

| 千 | 百 | 十 | 一 | |

| 上位(商) | 7 | 2 | ||

| 中位(实) | 2 | 6 | 1 | |

| 下位(法) | 9 |

(4) The upper 2 calls the lower 9: two nines are 18, so remove 180 from the numeral in the middle position.

| 千 | 百 | 十 | 一 | |

| 上位(商) | 7 | 2 | ||

| 中位(实) | 8 | 1 | ||

| 下位(法) | 9 |

(5) Once again shift the numeral in the lower position one place [to the right], and put down 9 in the upper position.

| 千 | 百 | 十 | 一 | |

| 上位(商) | 7 | 2 | 9 | |

| 中位(实) | 8 | 1 | ||

| 下位(法) | 9 |

(6) The upper 9 calls the lower 9: nine nines are 81, so remove 81 from the numeral in the middle position.

| 千 | 百 | 十 | 一 | |

| 上位(商) | 7 | 2 | 9 | |

| 中位(实) | ||||

| 下位(法) | 9 |

(7) There is now no numeral in the middle position. Put away the numeral in the lower position. The result in the upper position is what each person gets.

| 千 | 百 | 十 | 一 | |

| 上位(商) | 7 | 2 | 9 | |

| 中位(实) | ||||

| 下位(法) |

Legacy of Counting Rods

For much of Chinese history, especially from the Han to the Yuan dynasties (206 BC - 1368 AD), counting rods played an important role in the development of Chinese mathematics. The Chinese counting rods alongside gradually spread throughout the Sinosphere (Korea, Japan, and Vietnam). After the Yuan dynasty, counting rods fell into disuse in China, and were replaced by the abacus. New mathematical texts of the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644 AD) introduced new computation methods adapted to the abacus. This “mechanization” of computation coincided with the decline in the theoretical development of traditional Chinese mathematics. However, during the Edo period of Japan (1603 – 1867 AD), notable Japanese mathematicians continued the use of counting rods in their research (Figure 7). This blossoming tradition, called wasan (和算, “Japanese mathematics”), extended the developments of Chinese mathematics to new heights, rivalling the increasingly advanced European mathematics of the 17th and 18th centuries.

References

[1] 钱宝琮主编.《中国数学史》,北京:科学出版社,1964年。

[2] 纪志刚《孙子算经、张邱建算经、夏侯阳算经导读》, 武汉:湖北教育出版社,1999年。

[3] 郭书春《九章算术译注》,上海:上海古籍出版社,2009年。

[4] 李兆华《中国数学史基础》,天津:天津教育出版社,2010年。

[5] Martzloff, Jean-Claude. A History of Chinese Mathematics (English Translation). Spinger-Verlag. 1997, 2006.

[6] Yong, Lam Lay, & Ang, Tian Se. Fleeting Footsteps: Tracing the Conception of Arithmetic and Algebra in Ancient China, Revised Edition. World Scientific Publishing Company. 2004

[7] Wilkinson, Endymion. Chinese History: A New Manual, 4th Edition. Harvard University Press. 2015.