Tag: Source edit |

Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==Rates and the Jinyou Method== |

==Rates and the Jinyou Method== |

||

[[File:Rule-of-3-3.png|thumb|400x400px|Figure 1. The ''jin you'' method or "rule of three"]] |

[[File:Rule-of-3-3.png|thumb|400x400px|Figure 1. The ''jin you'' method or "rule of three"]] |

||

| − | The concept of |

+ | The concept of rate (率 ''lü'')<sup>[1]</sup> was highly important in ancient Chinese mathematics. We will later discover that the notion of rates is vital in explaining the reasoning behind traditional Chinese problems on arithmetic, linear equations, and geometry. One important method discussed in Chapter 2 of the ''Jiuzhang Suanshu'' is the ''jinyou'' method (今有术 ''jin you shu'') or ''jinyou'' rule. The ''jinyou'' method most likely arose from commercial transactions of antiquity, for every problem in this chapter dealt with the exchange of different grains that followed a defined market rate. The market rates are used to calculate an unknown quantity of grain. In the ''Jiuzhang Suanshu'', at the beginning of Chapter 2, there is a table of market rates of various grains provided for the reader, as well as a detailed description of the ''jinyou'' method. |

| + | |||

| + | [1] In ancient China, the mathematical concepts of ratio, rate, and proportion share the same character 率. This differs from the modern usage: 比 for ratio, 比率 for rate, and 比例 for proportion. |

||

{| class="fandom-table" |

{| class="fandom-table" |

||

|粟米之法: |

|粟米之法: |

||

| Line 57: | Line 59: | ||

:<math> x = \frac{r_2 \times y}{r_1} </math> |

:<math> x = \frac{r_2 \times y}{r_1} </math> |

||

| − | Over the centuries, knowledge of the ''jinyou'' method travelled along the Eurasian trade routes (often called the Silk Road), making its way to India, the Middle East, and Europe. In ancient India, the astronomer-mathematician Aryabhata (476 - 550 AD) formulated a method for calculating rates equivalent to the ''jinyou'' method. |

+ | Over the centuries, knowledge of the ''jinyou'' method travelled along the Eurasian trade routes (often called the Silk Road), making its way to India, the Middle East, and Europe. In ancient India, the astronomer-mathematician Aryabhata (476 - 550 AD) formulated a method for calculating rates equivalent to the ''jinyou'' method. Indian mathematicians called it ''Trairāśika'', which literally translates to the "rule of three quantities". For centuries, the mathematicians and merchants of Muslim empires and Renaissance Europe still refer this arithmetic method as the "rule of three". |

== '''Unit Conversions''' == |

== '''Unit Conversions''' == |

||

| Line 151: | Line 153: | ||

30 ''jin'' = 1 ''jun'' |

30 ''jin'' = 1 ''jun'' |

||

| − | 4 ''jun'' = 1 ''dan |

+ | 4 ''jun'' = 1 ''dan''<sup>[2]</sup> |

|} |

|} |

||

| − | + | [2] The character 石 is pronounced ''shi'' for stone, but is pronounced ''dan'' for the unit of measurement. |

|

<br /> |

<br /> |

||

Revision as of 07:49, 14 January 2022

By: Tao Steven Zheng (郑涛)

Rates and the Jinyou Method

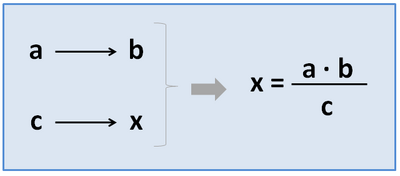

Figure 1. The jin you method or "rule of three"

The concept of rate (率 lü)[1] was highly important in ancient Chinese mathematics. We will later discover that the notion of rates is vital in explaining the reasoning behind traditional Chinese problems on arithmetic, linear equations, and geometry. One important method discussed in Chapter 2 of the Jiuzhang Suanshu is the jinyou method (今有术 jin you shu) or jinyou rule. The jinyou method most likely arose from commercial transactions of antiquity, for every problem in this chapter dealt with the exchange of different grains that followed a defined market rate. The market rates are used to calculate an unknown quantity of grain. In the Jiuzhang Suanshu, at the beginning of Chapter 2, there is a table of market rates of various grains provided for the reader, as well as a detailed description of the jinyou method.

[1] In ancient China, the mathematical concepts of ratio, rate, and proportion share the same character 率. This differs from the modern usage: 比 for ratio, 比率 for rate, and 比例 for proportion.

| 粟米之法:

粺米二十七;糳米二十四 御米二十一;小䵂十三半 大䵂五十四;粝饭七十五 粺饭五十四;糳饭四十八 御饭四十二;菽、荅、麻、麦各四十五 稻六十;豉六十三 飧九十;熟菽一百三半 蘖一百七十五

|

The regulated [rates of exchange] for grains:

Milled millet 27; Refined millet 24 Imperial millet 21; Refined wheat 13 ½ Coarse wheat 54; Cooked coarse wheat 75 Cooked milled millet 54; Cooked refined millet 48 Cooked imperial millet 42; Soy beans, Small beans, Sesame seed, Wheat 45 Paddy rice 60; Fermented soy beans 63 Porridge 90; Cooked beans 103 ½ Fermented grain 175

|

According to the above description, the jinyou method states that given two rates, the given rate and sought rate , and the given amount , one can determine the sought amount as follows:

Over the centuries, knowledge of the jinyou method travelled along the Eurasian trade routes (often called the Silk Road), making its way to India, the Middle East, and Europe. In ancient India, the astronomer-mathematician Aryabhata (476 - 550 AD) formulated a method for calculating rates equivalent to the jinyou method. Indian mathematicians called it Trairāśika, which literally translates to the "rule of three quantities". For centuries, the mathematicians and merchants of Muslim empires and Renaissance Europe still refer this arithmetic method as the "rule of three".

Unit Conversions

In actuality, the jinyou method is an abstract arithmetic principle related to rates and proportion. Knowing how the jinyou method can be used for calculating rates, one can apply this principle to the conversion of standardized units. In ancient China, there were three fundamental measures: linear measure (度 du), capacity measure (量 liang), and weight measure (衡 heng). The three tables below lists the conversion rates of progressively larger units, which will be used in the calculations for the problem studies.

Table 1. Linear Measure (度 du)

| 10 毫 = 1 厘

10 厘 = 1 分 10 分 = 1 寸 10 寸 = 1 尺 10尺 = 1 丈 6 尺 = 1 步 40 尺 = 1 匹(疋) 50 尺 = 1 端 300 步 = 1 里 |

10 hao = 1 li

10 li = 1 fen 10 fen = 1 cun 10 cun = 1 chi 10 chi = 1 zhang 6 chi = 1 bu 40 chi = 1 pi 50 chi = 1 duan 300 bu = 1 li |

Table 2. Capacity Measure (量 liang)

| 10 圭 = 1 撮

10 撮 = 1 抄 10 抄 = 1 勺 10 勺 = 1 合 10 合 = 1 升 10 升 = 1 斗 10 斗 = 1 斛 |

10 gui = 1 cuo

10 cuo = 1 chao 10 chao = 1 shao 10 shao = 1 ge 10 ge = 1 sheng 10 sheng = 1 dou 10 dou = 1 hu |

Table 3. Weight Measure (衡 heng)

| 10 絫 = 1 铢

24 铢 = 1 两 16 两 = 1 斤 30 斤 = 1 钧 4 钧 = 1 石 |

10 lei = 1 zhu

24 zhu = 1 liang 16 liang = 1 jin 30 jin = 1 jun 4 jun = 1 dan[2] |

[2] The character 石 is pronounced shi for stone, but is pronounced dan for the unit of measurement.

Problem Study 1: Exchanging Grains

The following problem is from the Jiuzhang Suanshu (Chapter 2, Problem 1).

| [2.01] 今有粟一斗,欲为粝米。问:得几何?

|

[2.01] Suppose the is 1 dou of millet, and one wishes to exchange it for hulled millet. Question: How much should there be?

|

Solution for [2.01]

Let denote the sought amount of hulled millet. From the table of capacity measures (Table 2), we find that 10 sheng (升) makes 1 dou (斗). Thus, the given amount is 10 sheng of millet. Referencing the market rates from Chapter 2 of the Jiuzhang Suanshu, we find that the exchange rate for millet is 50, and the exchange rate for hulled millet is 30. Substituting the given rates and the given amount of millet into the jinyou rule yields:

Problem Study 2: From Luoyang to Chang'an

The following problem is from the Sunzi Suanjing (Chapter 3, Problem 33).

| [3.33] 今有长安、洛阳相去九百里。车轮一匝一丈八尺。欲自洛阳至长安,问:轮匝几何?

术曰:置九百里,以三百步乘之,得二十七万步。又以六尺乘之,得一百六十二万尺。以车轮一丈八尺为法。除之,即得。

|

[3.33] Suppose the distance between Chang’an and Luoyang is 900 li. One rotation of the cart’s wheel measures 1 zhang 8 chi. Question: If one wishes to travel from Luoyang to Chang’an, how many rotations will the wheel make?

|

Solution for [3.33]

(1) Convert the distance between Luoyang (洛阳) and Chang’an (长安) from the unit li to chi.

1 li = 300 bu

1 bu = 6 chi

(2) Convert one rotation of the wheel into chi.

(3) Divide the distance between Luoyang and Chang’an by the circumference of one rotation.

References

[1] 钱宝琮主编.《中国数学史》,北京:科学出版社,1964年。

[2] 纪志刚《孙子算经、张邱建算经、夏侯阳算经导读》, 武汉:湖北教育出版社,1999年。

[3] 郭书春《九章算术译注》,上海:上海古籍出版社,2009年。

[4] 李兆华《中国数学史基础》,天津:天津教育出版社,2010年。

[5] Martzloff, Jean-Claude. A History of Chinese Mathematics (English Translation). Spinger-Verlag. 1997, 2006.

[6] Yong, Lam Lay, & Ang, Tian Se. Fleeting Footsteps: Tracing the Conception of Arithmetic and Algebra in Ancient China, Revised Edition. World Scientific Publishing Company. 2004

[7] Wilkinson, Endymion. Chinese History: A New Manual, 4th Edition. Harvard University Press. 2015.